Keep Public Lands Public

Posted: March 13, 2017Source: The Forest Blog

By: Russ Vaagen

Is it warranted? In my opinion, absolutely. If the federal government cannot figure out how to manage the lands for the benefits of all citizens, or as the Forest Service says “the greatest good for the greatest number of people,” then another solution will be created. If solutions aren’t brought to bear soon enough momentum could be created to insert new management or sell some of those lands to States, Counties, and other entities.

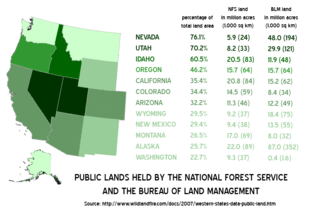

Rather than dissolve these great public lands, I think it deserves one more, good, honest try. What needs to be solved? We need more of the lands designed for management, active management. So many acres have essentially been in storage for the last 30 years. This has starved the forest industry to the point of extinction in parts of Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, California, and Nevada. These places have massive amounts of forested public land with roads and prior management, yet managers don’t have markets to sell even small projects. This results in a larger forest health problem that ultimately becomes a forest health nightmare. That nightmare shows up in the form of massive forest death from insect and disease, ultimately ending in a catastrophic wildfire.

Unfortunately, the debate has been between the people who love the outdoors and people who love to make a living working with forests. Most of the time these opposing views are talking about different landscapes. The forest industry isn’t interested in wilderness, national parks, or monuments. They want the opportunity to manage the lowland areas that have road systems and historic forest management. When outdoor enthusiasts hear that public lands might be sold off or given to the states a fear of loss sets in. The loss isn’t that the land near communities will be now managed at a more appropriate level. The loss is a fear that special recreational places will be sold off and developed.

We can have a robust forest management program and excellent recreational opportunities. It’s time that groups like the Outdoor Industry Association look to the forest industry as a partner. If recreation enthusiasts and public land lovers were for broad-based, sustainable forest management, a change would be inevitable. This is the way to protect the places that are most important to outdoor enthusiasts.

If we can do that, tackling other issues like effective, long-term grazing on public lands could be addressed as well. Avoiding these issues and ignoring them doesn’t help. The problem gets worse. We need a fair, open, and science-based dialog on these subjects. Doing things in an open setting with stakeholders participating is key. These kinds of discussions will require professional facilitation and ground rules. With open minds and empathy for other interests, I am certain we can create lasting solutions for all.

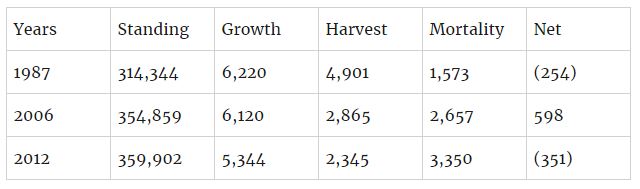

Forest management is the tool to keep forests in the public domain. It’s not a threat. I found some data put together by the USFS that is interesting. I believe it drives my point home. All volume in million cubic feet for the West.

From: USDA, Forest Service. 2014. US Forest Facts & Historical Trends, August 2014, page 24. https://www.fia.fs.fed.us/library/brochures/docs/2012/ForestFacts_1952-2012_English.pdf

This chart clearly demonstrates that we’ve missed the mark of sustainability. In the late 1980’s harvest levels on federal lands were at an all-time high. Mortality was down, but the combination of trees dying and trees harvested was more than the total growth. In 2006 the forests were still growing at a good rate, but the harvest level dropped and the mortality increased. The result of which was a net increase in standing volume, thus being sustainable. I do think that 2006 had reduced harvest too much as indicated by the 59% increase in mortality. That is evidenced by the numbers in 2012 which shows a mortality increase of more than double, while harvest levels dropped to less than half of what they were in 1987.

This chart demonstrates that we are missing a solution in the middle. It appears that we need harvest levels to be at a volume over 3 billion cubic feet. Please keep in mind, in 1987 the industry was not using top sizes under 8”, possibly down to 6”. Some of today’s most advanced small diameter mills use an average log size that is less than 7”. The point here is that much of today’s volume didn’t even exist 25 years ago. We can apply the types of harvest that the public supports while providing much-needed material to mills.

If we don’t do this, I think we will be facing a future that breaks our federal land into pieces. There’s a bigger push than you think asking for that to happen today. The only way to turn that tide is to remove what’s fueling it. Manage forests better and create better recreational opportunities for all types.