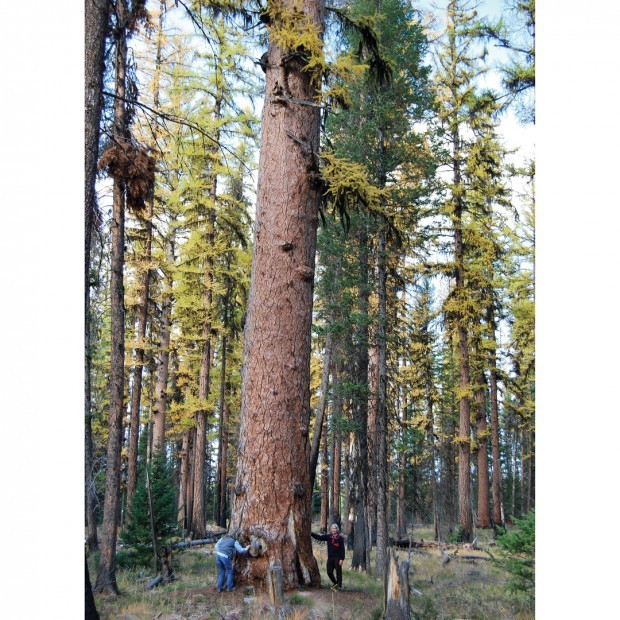

Meet Gus – World’s Largest Larch Tree

Posted: August 30, 2018Source: National Geographic

Trees grow big in the water-abundant Seeley-Swan valleys, but the granddaddy of them all is a 1,000-year-old western larch, known locally as Gus. A gentle, mile-long nature trail loops through the Girard Grove near the western shore of Seeley Lake.

There’s plenty of big trees in this 250-acre grove, averaging perhaps 600 years old, but Gus stands out as the champion. In fact, Gus appears to be the largest larch tree in the world among the 10 species found primarily in North America, Asia and Europe.

Although I’ve been unable to document a definitive claim of the world’s largest larch tree, it stands to reason since 1) Gus has been documented as the largest western larch (Larix occidentalis) of the 10 species, and 2) Western larch is the largest of the 10 Larix species. (Larch trees also are known as tamarack.) Gus is 163 feet high, plus another 10-foot dead top. It has a crown diameter of 34 feet, and a circumference of 273 inches.

The range of western larch is relatively small, and it tends to coincide closely with the Crown of the Continent region. The Canadian Flathead Valley (North Fork) and the South Fork of the Flathead watershed also are particularly great places to view larch, especially in the fall when this rarity of the conifer species drops its green-turned-golden needles, a faux-evergreen that’s really deciduous.

Western larch can also be found in some spots on the drier east side of the Continental Divide, such as in the Waterton Valley of Glacier and Waterton parks.

A bit to the west of the Crown of the Continent region, larch also grow large in northern Idaho and the Purcell Range of British Columbia and Montana, including the West Kootenay and Yaak Valley.

Forest ecologists document that old-growth western larch have survived a dozen or more low-intensity fires, some started by lightening and others by Native Americans hundreds of years ago. The tree’s thick bark creates a shield intended to survive fires, and its tiny seeds germinate and thrive under the ideal conditions of a post-fire forest.

Starting in the late 1890s, however, loggers and railroad companies began to fall the old giants like there was no tomorrow. Whereas nature and Indians would leave the biggest, healthiest trees, while cleaning out the thicker underbrush, latter-day humans were doing the exact opposite, taking the best trees and leaving the more flammable, small-diameter trees and brush.

In the few old-growth larch forests spared by loggers, such as the Girard Grove, aggressive fire suppression was creating dense forest conditions under which any fire that got away would probably torch the entire forest, including the granddaddies.

Fortunately, the Forest Service began to recognize the adverse impacts of fire supression and highgrade logging, and some visionary foresters began to follow nature’s lead through understory thinning and prescribed burning. The Seeley Lake Ranger District of the Lolo National Forest has been a leader in promoting restoration forestry.

You can view foresters’ light touch in the Girard Grove, which was commercially thinned by loggers in the mid-1990s, leaving a beautiful stand of old-growth larch that has regained its ability to survive the next wildfire. The huge larch trees in this area are protected in honor of Jim Girard, a forester and woodsman who once worked in the Seeley Lake area.

A second species of larch can be found in the Crown of the Continent, known as Lyall’s Larch or alpine larch (Larix lyallii), a remnant survivor of the ice age. It also is a long-lived species found primarily on windswept mountain ridges and sub-alpine bowls.

The luminescent green of the Lyall’s larch’s dainty needles stand out against the blackish trunks, a lovely contrast that is just as vivid when the needles turn golden yellow on those crisp October days that never cease to delight, when you know that you stand on top of the world.